Imagine the Rolling Stones’ classic “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” sans the embellishments of the London Bach Choir. Definitely doable, in my opinion. Ponder the Beatles’ “The Long and Winding Road,” minus the Phil Spector-imposed orchestral strings and choir of angels. Totally preferable. Contemplate Bob Dylan’s landmark “Like a Rolling Stone” without those haunting, no-direction-home Hammond organ chords. Absolutely inconceivable. Had it not been for the gutsy gamble of a 21-year old named Al Kooper, Dylan’s decade-defining anthem would lack much of its signature, soulful sound.

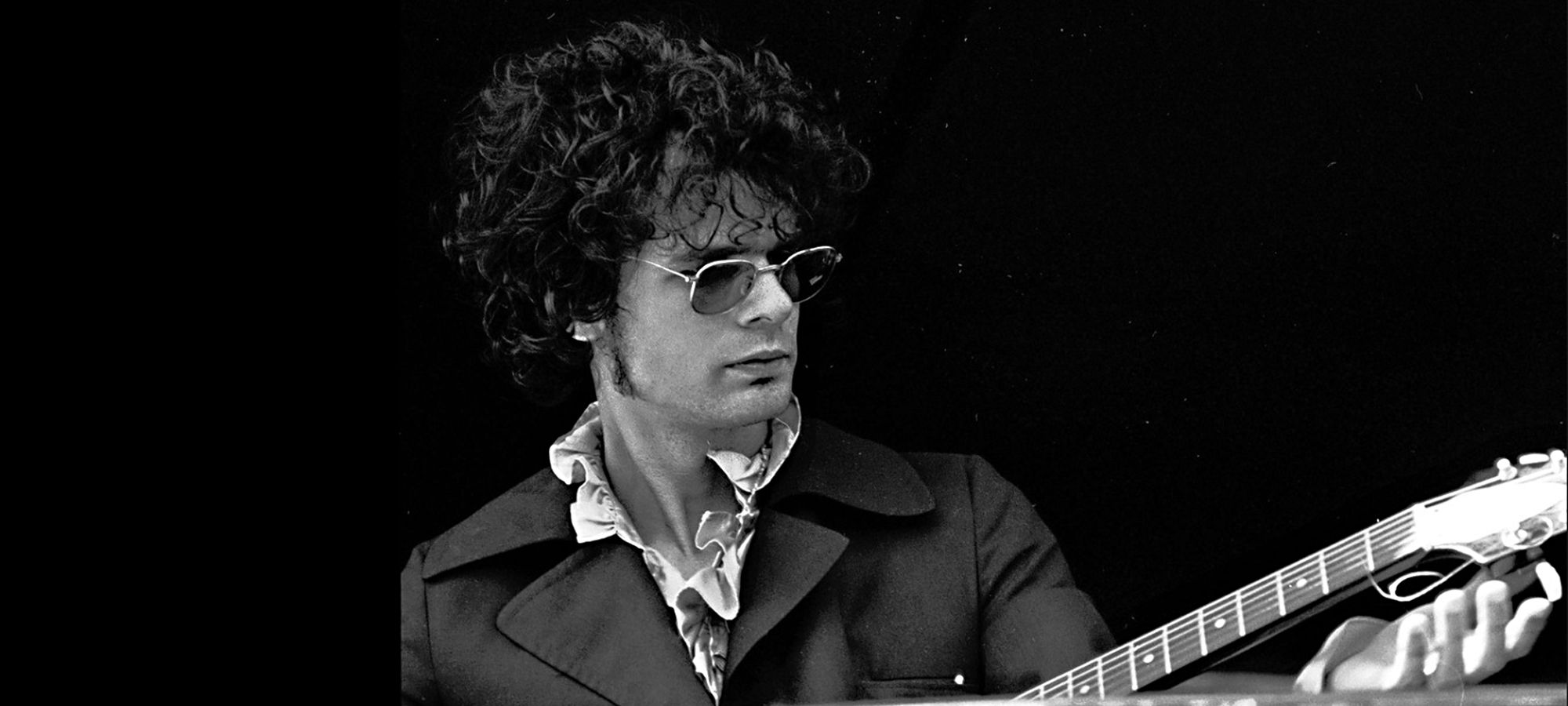

Young Alan Peter Kuperschmidt was scraping by as a Tin Pan Alley songwriter and budding rock musician when his friend, Columbia Records producer Tom Wilson, invited him to sit in on one of the most famous studio sessions of all time: the recording of Dylan’s first fully electric album (and my favorite LP of all time), “Highway 61 Revisited.” Says Kooper in his rollicking memoir, Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards – Memoirs of a Rock-n-Roll Survivor, “In 1965, being invited to a Bob Dylan session was like getting backstage passes to the fourth day of creation.”

Young Alan Peter Kuperschmidt was scraping by as a Tin Pan Alley songwriter and budding rock musician when his friend, Columbia Records producer Tom Wilson, invited him to sit in on one of the most famous studio sessions of all time: the recording of Dylan’s first fully electric album (and my favorite LP of all time), “Highway 61 Revisited.” Says Kooper in his rollicking memoir, Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards – Memoirs of a Rock-n-Roll Survivor, “In 1965, being invited to a Bob Dylan session was like getting backstage passes to the fourth day of creation.”

Still, Kooper was invited to observe, not play. But that didn’t stop the tenacious young man from bringing along his guitar in the hopes of scheming his way into recording history. “There was no way in hell I was going to visit a Bob Dylan session and just sit there pretending to be some reporter from Sing Out! magazine!” he said.

Before Tom Wilson entered the studio, Al had already unpacked, plugged in, and tuned up his guitar. What’s the worst that could happen? If Wilson balked, he’d just say he misunderstood his reason for being invited. Then, in walked a wild-looking character named Mike Bloomfield, Fender Telecaster in hand. His guitar warmups alone were impressive enough to convince the ever-confident Kooper that he was a mere piker in comparison. He sheepishly unplugged his guitar, retreated to the control room, and and sat contritely, “pretending to be a reporter from Sing Out! magazine.”

With God-almighty Dylan finally on the scene, a long day’s recording journey into night began, with the creation of a multi-verse narrative song called “Like a Rolling Stone.” Dylan, notorious for constantly changing his mind during sessions, decided that the organ part originally conceived for the song would be better suited to piano. When keyboardist Paul Griffin moved over to piano, Kooper made a last-ditch effort to jump in, begging Tom Wilson for a chance to tinker on the Hammond organ (an instrument he knew nothing about, by the way). Wilson told Kooper he’d only embarrass himself, then left the studio temporarily to tend to other business. Seizing the moment, Al quickly planted himself at the organ, and took the biggest leap of his life.

With God-almighty Dylan finally on the scene, a long day’s recording journey into night began, with the creation of a multi-verse narrative song called “Like a Rolling Stone.” Dylan, notorious for constantly changing his mind during sessions, decided that the organ part originally conceived for the song would be better suited to piano. When keyboardist Paul Griffin moved over to piano, Kooper made a last-ditch effort to jump in, begging Tom Wilson for a chance to tinker on the Hammond organ (an instrument he knew nothing about, by the way). Wilson told Kooper he’d only embarrass himself, then left the studio temporarily to tend to other business. Seizing the moment, Al quickly planted himself at the organ, and took the biggest leap of his life.

He plugged away, hesitantly playing by feel, with no sheet music, direction or acknowledgment. He carefully waited to hear the chords of the other instruments, then came in an eighth note behind his fellow musicians, whose music was so overpowering he could barely hear his own organ playing. When you listen closely to the completed masterpiece, you become aware of the timid naiveté of his playing. His chords are brilliant in their simplicity. During playback of one of the early takes, Dylan asked that the organ part be turned up. Tom Wilson did a head turn, quickly apologizing for Kooper’s antics. But the predictably unpredictable Bob always got his way, and Al’s impromptu performance was to become the stuff that rock legends are made of. Alan Kuperschmidt was now on the path to a long and interesting career.

Blessed with ability, charisma and loads of chutzpah, Kooper is one of rock’s most accomplished figures. He’s toured with Dylan several times, most notably in 1965 during Bob’s controversial all-electric early shows. (Contrary to popular belief, Al claims the folk purists booed Dylan at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival because the set was short and the sound was poor, not because it was electric).

Kopper went on to play keyboards in the psychedelic-blues jam band The Blues Project and founded the rock-blues-brass fusion group Blood, Sweat and Tears. He recorded one of the 1960s’ most respected blues jam albums – “Super Session” – with Mike Bloomfield. He’s released numerous solo LPs and has played everything from keyboards to guitar to French horn in sessions for George Harrison, the Stones, Jimi Hendrix, The Who, Joe Cocker, B.B. King, Alice Cooper, and Tom Petty.

Kopper went on to play keyboards in the psychedelic-blues jam band The Blues Project and founded the rock-blues-brass fusion group Blood, Sweat and Tears. He recorded one of the 1960s’ most respected blues jam albums – “Super Session” – with Mike Bloomfield. He’s released numerous solo LPs and has played everything from keyboards to guitar to French horn in sessions for George Harrison, the Stones, Jimi Hendrix, The Who, Joe Cocker, B.B. King, Alice Cooper, and Tom Petty.

And, he’s produced loads of albums, including Dylan’s “New Morning,” Lynyrd Skynyrd’s first three LPs, and the provocative debut album of bizarro band The Tubes. Along the way he’s found time to score music for Hal Ashby’s film “The Landlord,” John Waters’ movie “Cry Baby,” and Michael Mann’s TV series “Crime Story.” He’s even taught songwriting and record production courses at Berklee College of Music, and once formed a band with fellow professors called The Funky Faculty.

Through sheer ambition and audacity, Al Kooper kick-started his career by contributing a defining sound to the most influential rock song of the 20th century. But even without that lucky break he would never have been a complete unknown, thanks to his innate drive, quick wits, good taste, and sheer talent. His hilarious, must-read memoir, Backstage Passes, is an epic tale of a man who’s not only enjoyed the respect of his peers over the course of five decades, but has managed to survive drugging, personal illness, and the various backstabbing bastards of the sordid music business.

Click below to listen to “Like a Rolling Stone,” and experience the Hammond organ magic that Al brought to the song.

And, here’s Al on keyboards, with his friend, the late, great Mike Bloomfield, performing “Albert’s Shuffle” from their Super Session LP.

Dana Spiardi, Feb 5, 2014

Brilliant article. Of course, I never heard the organ before in the song. It’s a subtle undercurrent. My but that song is great; haunting, upsetting, wistful.