“What did you do in the war, Daddy?” That’s a question most kids eventually get around to asking when they learn their fathers served in the armed forces.

Almost all of my childhood friends had dads who served in either World War II or the Korean War. In those days it wasn’t uncommon for veterans to keep their war stories to themselves, especially those who fought in battle or witnessed atrocities. The men who went to war back then were of a generation steeped, for better or worse, in silent suffering. They shared a collective stiff-upper-lip consciousness. I remember being at the home of my friends Betty Jo and Ann, building a cage in the basement for our pet mouse Harvey, when we stumbled upon a small case containing a Purple Heart – a medal awarded to those wounded or killed while serving their country. My friends were surprised to discover it, and stunned that their dad, Perry, had never mentioned he was wounded.

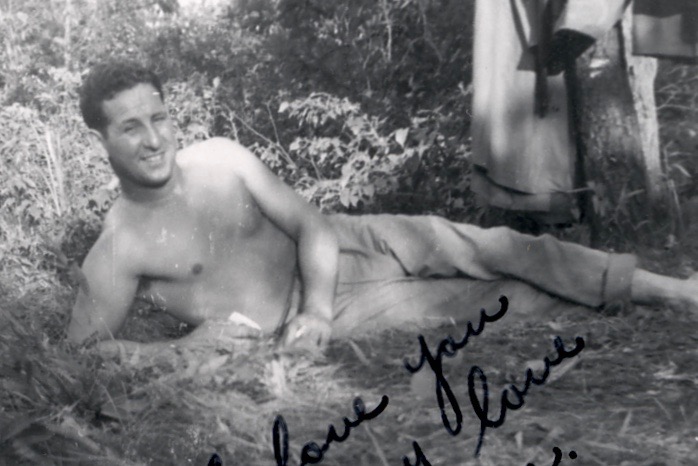

Well, my father was one of the lucky ones who returned from a foreign war with mind and body intact (albeit a somewhat exhausted liver). He was drafted to serve in the Korean War, departing from his hometown of Blairsville, PA, in December 1950. He managed to avoid serving on the front lines because he possessed a skill – auto mechanics – that landed him in the motor pool. His schooling in the world of engines, transmissions, shocks, and struts was driven more by need than a mere love of cars. To make some extra money for his family, my industrious dad asked the administrators at his school if he could leave classes a few hours early to work at Art Baker’s auto repair shop, a decades-old garage on North Walnut Street. Times were tough. My Italian immigrant grandparents raised five kids on a coal miner’s salary. They also made a little cash selling “Dago Red” wine that my grandmother Rose made in her basement. As a kid, my dad loaded the bottles into a wagon, covered the goods with a blanket, and peddled spirits through the streets of South Blairsville’s Italian neighborhood and the nearby company village known as Tin Town, on the banks of the Conemaugh River.

Well, my father was one of the lucky ones who returned from a foreign war with mind and body intact (albeit a somewhat exhausted liver). He was drafted to serve in the Korean War, departing from his hometown of Blairsville, PA, in December 1950. He managed to avoid serving on the front lines because he possessed a skill – auto mechanics – that landed him in the motor pool. His schooling in the world of engines, transmissions, shocks, and struts was driven more by need than a mere love of cars. To make some extra money for his family, my industrious dad asked the administrators at his school if he could leave classes a few hours early to work at Art Baker’s auto repair shop, a decades-old garage on North Walnut Street. Times were tough. My Italian immigrant grandparents raised five kids on a coal miner’s salary. They also made a little cash selling “Dago Red” wine that my grandmother Rose made in her basement. As a kid, my dad loaded the bottles into a wagon, covered the goods with a blanket, and peddled spirits through the streets of South Blairsville’s Italian neighborhood and the nearby company village known as Tin Town, on the banks of the Conemaugh River.

PFC Spiardi didn’t come home with any horror stories from the war — just a few tales of bad hangovers and one account that involved the time he almost lost several frostbitten toes during the brutal Korean winter of 1951. I was intrigued by his traumatized toenails. They always looked like small stalks of wilted celery.

PFC Spiardi didn’t come home with any horror stories from the war — just a few tales of bad hangovers and one account that involved the time he almost lost several frostbitten toes during the brutal Korean winter of 1951. I was intrigued by his traumatized toenails. They always looked like small stalks of wilted celery.

As a toddler he’d get my attention by calling out, idi-wa, which was Korean for “hey, come here.” And he’d beckon me to him, Asian-style, by extending his arm in an overhand fashion and wiggling his fingers forward and back.

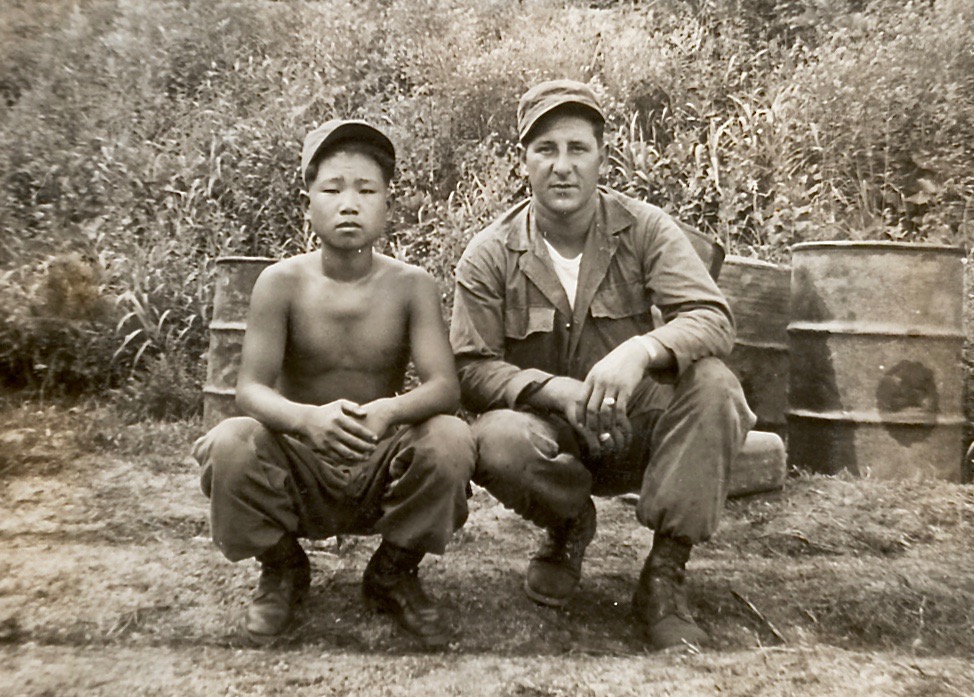

He liked to toss around a few other phrases he’d picked up from the division’s houseboy, Kim, who ran errands for the soldiers and carried out chores like doing laundry. Takusan meant “a lot” and chisai mean “small,” and that’s how the motor pool boys indicated their preferred serving sizes in the chow line. (Years later, while living in Tokyo, I discovered Daddy had actually been speaking Japanese, the language Koreans were forced to learn during Japan’s occupation of their country.)

He liked to toss around a few other phrases he’d picked up from the division’s houseboy, Kim, who ran errands for the soldiers and carried out chores like doing laundry. Takusan meant “a lot” and chisai mean “small,” and that’s how the motor pool boys indicated their preferred serving sizes in the chow line. (Years later, while living in Tokyo, I discovered Daddy had actually been speaking Japanese, the language Koreans were forced to learn during Japan’s occupation of their country.)

Being in the motor pool provided a soldier marooned in the Korean countryside with numerous opportunities, one of which involved the chance to temporarily escape the grim surroundings by driving a company jeep to and from Seoul to transport people and assorted goods. Daddy was not only an imbiber of alcohol, but an enterprising one, at that. During his brief stop-overs in the capital city, he’d buy a few bottles of choice liquor, take it back to camp, and make a profit selling it to his buddies.

But his most memorable story involved the time he was sent to Seoul to pick up an important colonel and take him to his destination. Daddy arrived a bit early, met up with his liquor connection, and threw back a few too many. When the colonel approached the jeep for his journey north toward the 38th parallel, he quickly noticed my dad’s inebriated state and said, “Private, you’re drunk. You’re not driving me in that condition.” Given the time constraints and the lack of another driver, the colonel could think of only one solution: He would drive the jeep wearing Daddy’s helmet and army jacket, and Daddy would don the colonel’s hat and winter topcoat and sit in the passenger seat. As the jeep pulled away from the base, soldiers along the road saluted my dad, who saluted back. It was like a scene from a farcical army film.

But his most memorable story involved the time he was sent to Seoul to pick up an important colonel and take him to his destination. Daddy arrived a bit early, met up with his liquor connection, and threw back a few too many. When the colonel approached the jeep for his journey north toward the 38th parallel, he quickly noticed my dad’s inebriated state and said, “Private, you’re drunk. You’re not driving me in that condition.” Given the time constraints and the lack of another driver, the colonel could think of only one solution: He would drive the jeep wearing Daddy’s helmet and army jacket, and Daddy would don the colonel’s hat and winter topcoat and sit in the passenger seat. As the jeep pulled away from the base, soldiers along the road saluted my dad, who saluted back. It was like a scene from a farcical army film.

Do you believe the story? Well, I do. I never knew my dad to tell any tall tales of that nature. He didn’t HAVE to. His outgoing, mischievous nature afforded him plenty of interesting experiences and stories. And he delivered them all in expletive-rich language that would make you laugh and sometimes blush. When he was on stage, anything was fair game.

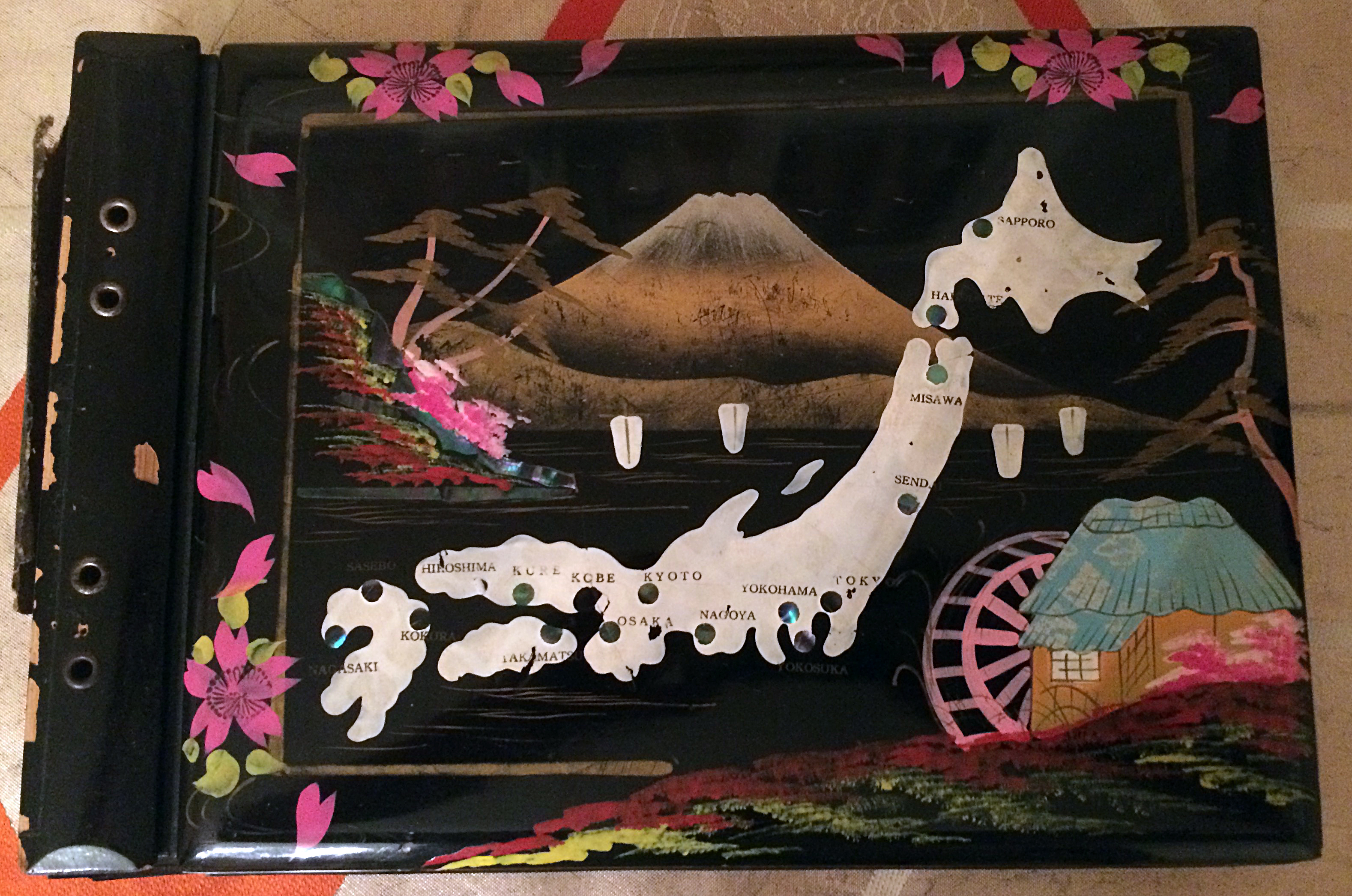

As a kid, I was fascinated by a gorgeous lacquered photo album Daddy bought during a trip to Tokyo for R&R. He filled it with pictures of himself and his buddies. He also preserved the many photos he took of barren landscapes, war-weary women, hungry children in ragged clothes, and even a stray dog that became the troop mascot. He talked a lot about the impoverished Koreans he encountered. Like all American soldiers, he gave them candy and other treats. Daddy was particularly fond of the houseboy Kim, and always wondered what became of him.

As a kid, I was fascinated by a gorgeous lacquered photo album Daddy bought during a trip to Tokyo for R&R. He filled it with pictures of himself and his buddies. He also preserved the many photos he took of barren landscapes, war-weary women, hungry children in ragged clothes, and even a stray dog that became the troop mascot. He talked a lot about the impoverished Koreans he encountered. Like all American soldiers, he gave them candy and other treats. Daddy was particularly fond of the houseboy Kim, and always wondered what became of him.

That lacquered album is one of my prized possessions. It’s so pretty that I have it displayed behind glass in my dining room. Its delicate spine is broken, which makes it all the more special to me. I handle it gingerly. And here’s what really gets to me: I can still smell the glue that Daddy used to affix the photos to the black paper – each page separated by a sheet of thin, marbled rice paper.

I had several opportunities to visit Korea in the 1990s. I took loads of photos so that I could show my dad how Seoul had grown into a world-class city. Over the years I visited all the museums, road the subways, fell in love with kimchi, bought lots of cheap leather goods in the famous Itaewon market, and even took a USO-sponsored trip to the DMZ in Panmunjom, where I stood at the border with one foot in the South and one foot in the North, gazing at the alien emptiness of the world’s most secretive country.

Once, in a park in Seoul, I heard a woman summon her pretty little girl by calling out, “Idi-wa.” I took pause, and remembered how I went running to Daddy when I heard those words.

My dad didn’t do anything really special during the war. He earned no medals or commendations. He kept the jeeps running, the laughs coming, and the liquor flowing. But, more importantly, he had a sharp eye for detail, vivid memories of the people he met, and a big heart full of compassion. And that’s heroic enough for me.

© Dana Spiardi, May 30, 2016

“What Did You Do in the War, Daddy” was the title of a silly 1966 film about a band of U.S. soldiers trying to convince the citizens of a small Sicilian village to surrender to the Germans during WWII. Director Blake Edwards came up with the title after his son posed that question. The film starred James Coburn and Dick Shawn.

Lovely. I can see it all in my mind, thanks to your description and a few photos .

I also think that your dads great love of storytelling and photography has its legacy in you. Dare I say, “cheers”. Thanks.

Great story. So you come from a family of bootleggers, what other family secrets you hidin’? I won’t tell.