Ah, you always remember your first time. There I was, in a dimly lit room…body tense and trembling under crisp sheets…heartbeat wild in anticipation…breaths short and shallow…spellbound by my first glimpse of something big, scary, and invasive…a spectacle that would excite me for the rest of my life: the 1935 classic, “The Bride of Frankenstein.”

I had already been wowed by the film’s predecessor: the 1931 thriller about a doctor named Frankenstein who assembles a man from the body parts of the dead, using safe, clean, affordable electricity to bring him to life. At first the bolt-necked patchwork creation appears docile — like a frightened stray dog, able to obey simple commands. But soon he’s spooked by the sight of a torch, and all hell breaks loose. Branded a monster, he’s chained to dungeon walls, taunted with fire, hunted down by thick-witted peasants, forced to wear drab, ill-fitting clothes, and denied even the most rudimentary instruction in diction, decorum, and the dangers of tossing one’s playmates into the pond. No wonder he was grumpy.

I had already been wowed by the film’s predecessor: the 1931 thriller about a doctor named Frankenstein who assembles a man from the body parts of the dead, using safe, clean, affordable electricity to bring him to life. At first the bolt-necked patchwork creation appears docile — like a frightened stray dog, able to obey simple commands. But soon he’s spooked by the sight of a torch, and all hell breaks loose. Branded a monster, he’s chained to dungeon walls, taunted with fire, hunted down by thick-witted peasants, forced to wear drab, ill-fitting clothes, and denied even the most rudimentary instruction in diction, decorum, and the dangers of tossing one’s playmates into the pond. No wonder he was grumpy.

Flash forward to the monster’s second feature film. Despite his expanding vocabulary, he’s as lonely and misunderstood as ever. He demands his now-estranged creator build him a friend — better yet, a bride!

Soon, the laboratory is once again abuzz with activity, as Dr. Frankenstein and his mad mentor Dr. Pretorius giddily rev up the machinery. Bones and organs arrive by FedEx. Fashion designers line up at the door, all vying to be the bride’s official dressmaker. Tabloid photographers position their cameras at filthy windows. (Well, that’s how it would play out today, you know.)

At last the scientists unveil their new creation: a willowy femme fatale in a makeshift Grecian gown, her head design inspired by Nefertiti, her hair embellished with fabulous lightening bolt streaks. I couldn’t take my eyes off her! And neither could the monster, as he descends the stairs to the eerie lab, cautiously optimistic.

At last the scientists unveil their new creation: a willowy femme fatale in a makeshift Grecian gown, her head design inspired by Nefertiti, her hair embellished with fabulous lightening bolt streaks. I couldn’t take my eyes off her! And neither could the monster, as he descends the stairs to the eerie lab, cautiously optimistic.

“Friend?” he pleads tenderly, as he staggers toward her with outstretched hands. In robotic motion, she cranes her cross-stitched neck, swivels her prominent head, fixes her frozen doll-eyes upon him, and lets out a shriek that could wake the…whatever. Undeterred, he follows her across the room to a bench. Smiling timidly, he lifts her thin gauze-wrapped arm and gently pats her long withered fingers. She drops her jaw, screams into his face, and recoils. The monster is devastated. His facial expression dissolves from joy to sadness to rage in the course of 5 seconds. “She hate me…like others,” he grunts, and proceeds to blow up the laboratory, taking the snooty bride and crazy Dr. Pretorius along with him as he returns to the dead. What a grand way to end the worst first date in history. Such unbridled, passionate vengeance! A true existentialist’s delight!

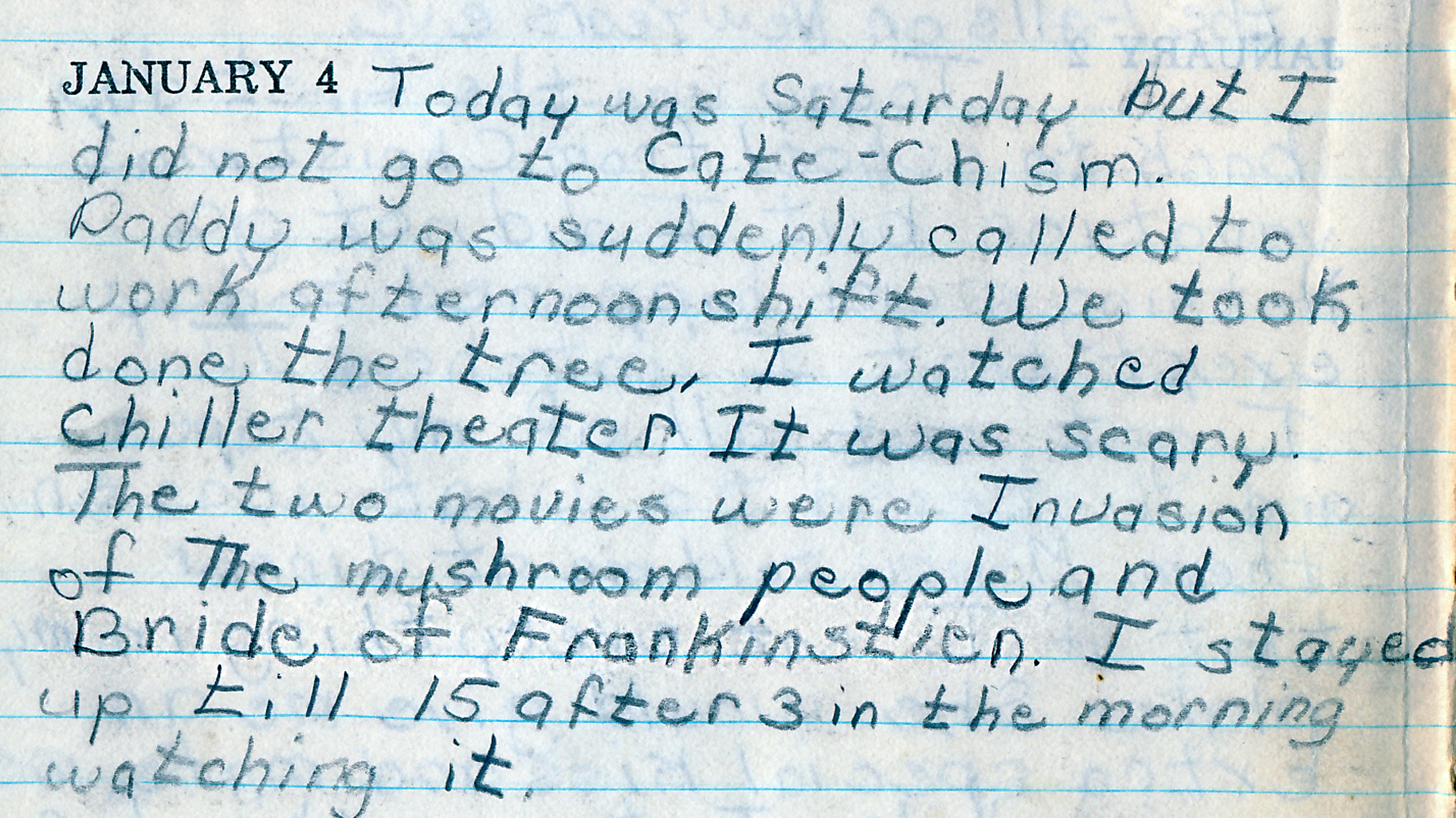

I was terribly moved by this scene. In fact, I was completely verklempt by the entire production, even noting it in my diary, January 4, 1969 (“Chiller Theater” was my midnight catechism). At age 9, already a night owl…an only-child feeling isolated and misunderstood…I strongly identified with the monster’s emotions.

I was terribly moved by this scene. In fact, I was completely verklempt by the entire production, even noting it in my diary, January 4, 1969 (“Chiller Theater” was my midnight catechism). At age 9, already a night owl…an only-child feeling isolated and misunderstood…I strongly identified with the monster’s emotions.

This cinematic masterpiece introduced me to societal rejection, unrequited love, mob mentality, and the tortured soul of the outcast. The monster was to spend his days friendless, sexless, and reviled — simply because no one cared or dared to see past his rough features and undeveloped communication skills.

In fact, this film launched my lifelong love of antihero movies: “Cool Hand Luke,” “Midnight Cowboy,” “Dog Day Afternoon,” “Edward Scissorhands” — all films that end with the sad death or defeat of a misfit, a scapegoat, a would-be contender, a beautiful loser.

Much has been written about the monster first introduced on the pages of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein. The creature has been the subject of more than 70 films since 1910. Cinema buffs and sociologists have long analyzed the biblical, homosexual, and megalomaniacal subtexts of many of these movies.

Much has been written about the monster first introduced on the pages of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein. The creature has been the subject of more than 70 films since 1910. Cinema buffs and sociologists have long analyzed the biblical, homosexual, and megalomaniacal subtexts of many of these movies.

And while the casual viewer might dismiss the 1931 “Frankenstein” and its “Bride” sequel as nothing more than campy entertainment, serious lovers of the art of film all agree that when it comes to the archetypical monster movie, nothing compares to the visual, soul-stirring spectacle of those two magnificent thrillers. (Not to mention the bride’s hairdo, which yer blogger will be dreaming about forever.)

Here’s the famous scene of the monster couple’s first and last date. Both “Frankenstein” and “Bride of Frankenstein” were directed by the great James Whale, Hollywood’s first openly gay director. Boris Karloff (born William Henry Pratt) plays the monster. Elsa Lanchester, as the bride, wore stilts to appear 7 feet tall. Colin Clive, who succumbed to alcoholism at age 37, plays the manic Henry Frankenstein. But the actor who steals the show and adds a dose of comic relief is Ernest Thesinger as Dr. Pretorius. Pay attention to the superb editing (by Ted J. Kent) in the final moments before the teary-eyed monster “blows them all to atoms.” The bride bids farewell with one final hiss. This is one of my favorite movie scenes of all time.

© Dana Spiardi, Nov 1, 2013

Great story. Read like something you wanted to write when you felt like writing it.

Beautifully written, enjoyable, and informative piece. Nice work!

Wow, thanks, I get it now. Frankenstein is really the story of a guy who gets his heart broken by a female monster. SEE, you women ain’t no damn good. Except for you Dana, of course.

Fascinating. I would not have ever noticed. And thanks to you, I Frankenstein watched it.

Dana interesting take on Frankenstein movie and how you related to it. I did not know you at your tender age of 9, but what is important is that you are a survivor.

Sweet and heartwarming diary excerpt. You knew at an early age what was fascinating. Way to go and grow.

Is The Bride actually supposed to be 7 foot tall or is that some kind of urban myth as Lanchester appears only slightly taller than Colin Clive in the film?