Almost all of my childhood friends had dads who served in either World War II or the Korean War. In those days it wasn’t uncommon for veterans to keep their war stories to themselves, especially those who fought in battle or witnessed atrocities. The men who went to war back then were of a generation steeped, for better or worse, in silent suffering. They shared a collective stiff-upper-lip consciousness. I remember being at the home of my friends Betty Jo and Ann, building a cage in the basement for our pet mouse Harvey, when we stumbled upon a small case containing a Purple Heart – a medal awarded to those wounded or killed while serving their country. My friends were surprised to discover it, and stunned that their dad, Perry, had never mentioned he was wounded.

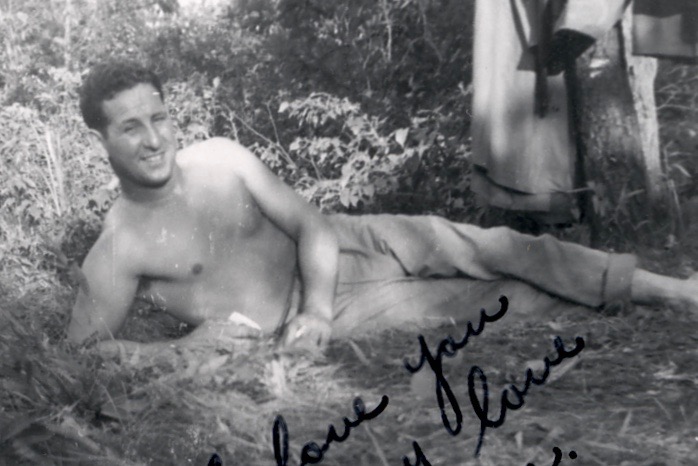

Well, my father was one of the lucky ones who returned from a foreign war with mind and body intact (albeit a somewhat exhausted liver). He was drafted to serve in the Korean War, departing from his hometown of Blairsville, PA, in December 1950. He managed to avoid serving on the front lines because he possessed a skill – auto mechanics – that landed him in the motor pool. His schooling in the world of engines, transmissions, shocks, and struts was driven more by need than a mere love of cars. To make some extra money for his family, my industrious dad asked the administrators at his school if he could leave classes a few hours early to work at Art Baker’s auto repair shop, a decades-old garage on North Walnut Street. Times were tough. My Italian immigrant grandparents raised five kids on a coal miner’s salary. They also made a little cash selling “Dago Red” wine that my grandmother Rose made in her basement. As a kid, my dad loaded the bottles into a wagon, covered the goods with a blanket, and peddled spirits through the streets of South Blairsville’s Italian neighborhood and the nearby company village known as Tin Town, on the banks of the Conemaugh River.

Well, my father was one of the lucky ones who returned from a foreign war with mind and body intact (albeit a somewhat exhausted liver). He was drafted to serve in the Korean War, departing from his hometown of Blairsville, PA, in December 1950. He managed to avoid serving on the front lines because he possessed a skill – auto mechanics – that landed him in the motor pool. His schooling in the world of engines, transmissions, shocks, and struts was driven more by need than a mere love of cars. To make some extra money for his family, my industrious dad asked the administrators at his school if he could leave classes a few hours early to work at Art Baker’s auto repair shop, a decades-old garage on North Walnut Street. Times were tough. My Italian immigrant grandparents raised five kids on a coal miner’s salary. They also made a little cash selling “Dago Red” wine that my grandmother Rose made in her basement. As a kid, my dad loaded the bottles into a wagon, covered the goods with a blanket, and peddled spirits through the streets of South Blairsville’s Italian neighborhood and the nearby company village known as Tin Town, on the banks of the Conemaugh River.

PFC Spiardi didn’t come home with any horror stories from the war — just a few tales of bad hangovers and one account that involved the time he almost lost several frostbitten toes during the brutal Korean winter of 1951. I was intrigued by his traumatized toenails. They always looked like small stalks of wilted celery.

PFC Spiardi didn’t come home with any horror stories from the war — just a few tales of bad hangovers and one account that involved the time he almost lost several frostbitten toes during the brutal Korean winter of 1951. I was intrigued by his traumatized toenails. They always looked like small stalks of wilted celery.

As a toddler he’d get my attention by calling out, idi-wa, which was Korean for “hey, come here.” And he’d beckon me to him, Asian-style, by extending his arm in an overhand fashion and wiggling his fingers forward and back.

He liked to toss around a few other phrases he’d picked up from the division’s houseboy, Kim, who ran errands for the soldiers and carried out chores like doing laundry. Takusan meant “a lot” and chisai mean “small,” and that’s how the motor pool boys indicated their preferred serving sizes in the chow line. (Years later, while living in Tokyo, I discovered Daddy had actually been speaking Japanese, the language Koreans were forced to learn during Japan’s occupation of their country.)

He liked to toss around a few other phrases he’d picked up from the division’s houseboy, Kim, who ran errands for the soldiers and carried out chores like doing laundry. Takusan meant “a lot” and chisai mean “small,” and that’s how the motor pool boys indicated their preferred serving sizes in the chow line. (Years later, while living in Tokyo, I discovered Daddy had actually been speaking Japanese, the language Koreans were forced to learn during Japan’s occupation of their country.)

Being in the motor pool provided a soldier marooned in the Korean countryside with numerous opportunities, one of which involved the chance to temporarily escape the grim surroundings by driving a company jeep to and from Seoul to transport people and assorted goods. Daddy was not only an imbiber of alcohol, but an enterprising one, at that. During his brief stop-overs in the capital city, he’d buy a few bottles of choice liquor, take it back to camp, and make a profit selling it to his buddies.

But his most memorable story involved the time he was sent to Seoul to pick up an important colonel and take him to his destination. Daddy arrived a bit early, met up with his liquor connection, and threw back a few too many. When the colonel approached the jeep for his journey north toward the 38th parallel, he quickly noticed my dad’s inebriated state and said, “Private, you’re drunk. You’re not driving me in that condition.” Given the time constraints and the lack of another driver, the colonel could think of only one solution: He would drive the jeep wearing Daddy’s helmet and army jacket, and Daddy would don the colonel’s hat and winter topcoat and sit in the passenger seat. As the jeep pulled away from the base, soldiers along the road saluted my dad, who saluted back. It was like a scene from a farcical army film.

But his most memorable story involved the time he was sent to Seoul to pick up an important colonel and take him to his destination. Daddy arrived a bit early, met up with his liquor connection, and threw back a few too many. When the colonel approached the jeep for his journey north toward the 38th parallel, he quickly noticed my dad’s inebriated state and said, “Private, you’re drunk. You’re not driving me in that condition.” Given the time constraints and the lack of another driver, the colonel could think of only one solution: He would drive the jeep wearing Daddy’s helmet and army jacket, and Daddy would don the colonel’s hat and winter topcoat and sit in the passenger seat. As the jeep pulled away from the base, soldiers along the road saluted my dad, who saluted back. It was like a scene from a farcical army film.

Do you believe the story? Well, I do. I never knew my dad to tell any tall tales of that nature. He didn’t HAVE to. His outgoing, mischievous nature afforded him plenty of interesting experiences and stories. And he delivered them all in expletive-rich language that would make you laugh and sometimes blush. When he was on stage, anything was fair game.

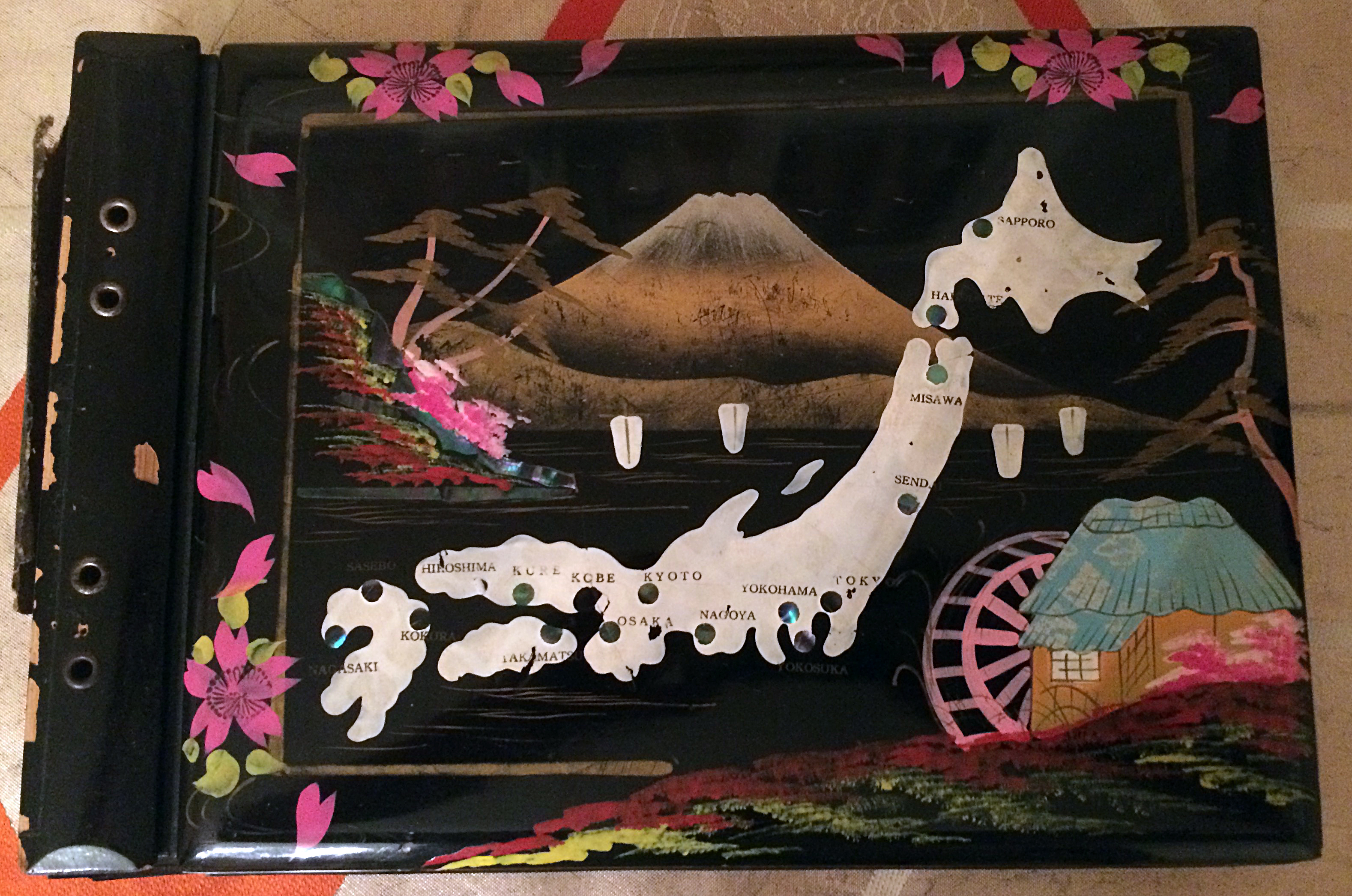

As a kid, I was fascinated by a gorgeous lacquered photo album Daddy bought during a trip to Tokyo for R&R. He filled it with pictures of himself and his buddies. He also preserved the many photos he took of barren landscapes, war-weary women, hungry children in ragged clothes, and even a stray dog that became the troop mascot. He talked a lot about the impoverished Koreans he encountered. Like all American soldiers, he gave them candy and other treats. Daddy was particularly fond of the houseboy Kim, and always wondered what became of him.

As a kid, I was fascinated by a gorgeous lacquered photo album Daddy bought during a trip to Tokyo for R&R. He filled it with pictures of himself and his buddies. He also preserved the many photos he took of barren landscapes, war-weary women, hungry children in ragged clothes, and even a stray dog that became the troop mascot. He talked a lot about the impoverished Koreans he encountered. Like all American soldiers, he gave them candy and other treats. Daddy was particularly fond of the houseboy Kim, and always wondered what became of him.

That lacquered album is one of my prized possessions. It’s so pretty that I have it displayed behind glass in my dining room. Its delicate spine is broken, which makes it all the more special to me. I handle it gingerly. And here’s what really gets to me: I can still smell the glue that Daddy used to affix the photos to the black paper – each page separated by a sheet of thin, marbled rice paper.

I had several opportunities to visit Korea in the 1990s. I took loads of photos so that I could show my dad how Seoul had grown into a world-class city. Over the years I visited all the museums, road the subways, fell in love with kimchi, bought lots of cheap leather goods in the famous Itaewon market, and even took a USO-sponsored trip to the DMZ in Panmunjom, where I stood at the border with one foot in the South and one foot in the North, gazing at the alien emptiness of the world’s most secretive country.

I had several opportunities to visit Korea in the 1990s. I took loads of photos so that I could show my dad how Seoul had grown into a world-class city. Over the years I visited all the museums, road the subways, fell in love with kimchi, bought lots of cheap leather goods in the famous Itaewon market, and even took a USO-sponsored trip to the DMZ in Panmunjom, where I stood at the border with one foot in the South and one foot in the North, gazing at the alien emptiness of the world’s most secretive country.

Once, in a park in Seoul, I heard a woman summon her pretty little girl by calling out, “Idi-wa.” I took pause, and remembered how I went running to Daddy when I heard those words.

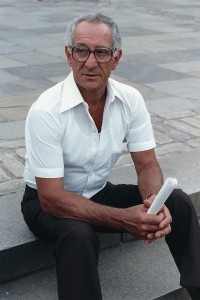

My dad didn’t do anything really special during the war. He earned no medals or commendations. He kept the jeeps running, the laughs coming, and the liquor flowing. But, more importantly, he had a sharp eye for detail, vivid memories of the people he met, and a big heart full of compassion. And that’s heroic enough for me.

© Dana Spiardi, May 30, 2016

“What Did You Do in the War, Daddy” was the title of a silly 1966 film about a band of U.S. soldiers trying to convince the citizens of a small Sicilian village to surrender to the Germans during WWII. Director Blake Edwards came up with the title after his son posed that question. The film starred James Coburn and Dick Shawn.

]]>

My dad, Fred Spiardi, started working at the Westinghouse Specialty Metals factory in Blairsville, PA, in 1956. For 14 years he performed a variety of jobs on the shop floor, never missing an opportunity to work overtime – including the “hoot owl” shift, which is what he called the midnight to 8 a.m. slot. In April of 1969, Westinghouse promoted him and several of his co-workers to supervisory positions, and sent the newly minted managers to division headquarters near Pittsburgh for 5 days of training.

My dad, Fred Spiardi, started working at the Westinghouse Specialty Metals factory in Blairsville, PA, in 1956. For 14 years he performed a variety of jobs on the shop floor, never missing an opportunity to work overtime – including the “hoot owl” shift, which is what he called the midnight to 8 a.m. slot. In April of 1969, Westinghouse promoted him and several of his co-workers to supervisory positions, and sent the newly minted managers to division headquarters near Pittsburgh for 5 days of training.

At the end of the week, the company treated the class to dinner and a show at The Holiday House, a 1,000 seat Vegas-style nightclub that attracted some of the country’s top national acts back in its heyday. The headliner on that particular Friday night was the queen of comedy, Phyllis Diller, a performer whose live act was a bit racier than her TV appearances.

Like Phyllis, my dad had a reputation as a cutup. He was a fearless extrovert who loved to command the room and generate laughs (and blushes) with his funny stories and off-color language. No one was spared a little ribbing when Daddy was around. So, before the show, his fellow supervisors decided to have a little fun at his expense. Someone managed to pass a note to Phyllis, asking her to harass a member of the audience named Freddie Baby.

Imagine my dad’s surprise when Phyllis, with her bird legs, electrostatic hair, garish outfit and jeweled cigarette holder, walked to the edge of the stage and asked, “Where’s Freddie Baby?”

Everyone in Daddy’s entourage pointed at him. And now it was his turn to blush, as Phyllis spent the next 30 seconds inviting him to engage in some type of lewd activity. The crowd loved it. And Daddy loved it, too. Because for that brief moment he was the center of attention. And that’s always where my proud Leo the Lion father felt most comfortable – in the spotlight.

Everyone in Daddy’s entourage pointed at him. And now it was his turn to blush, as Phyllis spent the next 30 seconds inviting him to engage in some type of lewd activity. The crowd loved it. And Daddy loved it, too. Because for that brief moment he was the center of attention. And that’s always where my proud Leo the Lion father felt most comfortable – in the spotlight.

R.I.P. Fabulous Phyllis! July 17, 1917 – August 20, 2012

R.I.P. Fabulous Daddy! August 4, 1928 – October 7, 2003

© Dana Spiardi, July 17, 2015

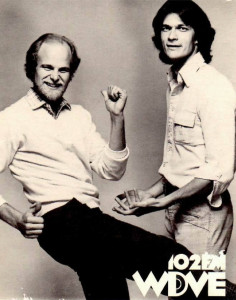

]]>I found relief in the form of a morning radio show on the prime Pittsburgh rock station WDVE, 102.5 FM. The “DVE Morning Alternative” was hosted by two very funny guys — “Little Jimmy” Roach and “Big Steve” Hansen — who provided entertainment during our long commute on a three-lane highway. There were two rules in the car: I couldn’t play the radio at wall-of-sound immersion levels, and I had to let Daddy listen to the sleeps-6-in-the-trunk-Buick of radio stations – the mighty megahertz KDKA 1020 AM – during the drive home.

Some of my fondest memories are of these times spent riding with my dad, gauging his reaction to the hits of the day and Jimmy and Steve’s slightly off-color skits. “Those dirty bastards,” he’d chortle at the duo’s double-entendres.

He never failed to comment on Wall of Voodoo’s “Mexican Radio” song, with its line, I wish I was in Tijuana, eating barbecued iguana. “That’s just silly,” he’d say as he lit a cigarette. “Nobody eats iguana!”

“Oh, not this again,” was his reaction each time he heard The Pretenders’ bluesy “My City Was Gone,” with the cool Chrissie Hynde lamenting, Ay, oh, where did you go, Ohio? “Where does she think it went?” he’d say. “Who told that girl she could sing? Hell, they’ll let anybody on the radio these days.” It didn’t matter to Daddy that I wanted to BE Chrissie Hynde at the time.

A strange tune called “Everywhere That I’m Not” by a group called Translator also annoyed him. “This is just stupid. Why do people write songs like this?” he’d say each time he heard these lyrics:

‘Cause you’re in New York, but I’m not.

You’re in Tokyo, but I’m not.

You’re in Nova Scotia, but I’m not.

Yeah, you’re everywhere that I’m not

I tried to explain that it was punk poetry, but he wasn’t buying it. (Can’t say that I blame him.)

But the biggest offender was Steely Dan’s “Kid Charlemagne,” with its reference to all those Day-Glo freaks who used to paint their face. “Why are they saying Dago freaks?” demanded my first-generation Italian father. I tried to explain that he misheard the lyric — that Day-Glo was a brand of brightly-colored fluorescent paint, and how this song chronicled the career of a famous LSD chemist named Owsley. But this was clearly too much information. He did, however, appreciate my explanation of the origin of the group’s name: Steely Dan was the moniker of a steam powered dildo in William Burroughs’ book “The Naked Lunch.” (I was always so happy that I could talk openly with my parents about anything and everything.)

But the biggest offender was Steely Dan’s “Kid Charlemagne,” with its reference to all those Day-Glo freaks who used to paint their face. “Why are they saying Dago freaks?” demanded my first-generation Italian father. I tried to explain that he misheard the lyric — that Day-Glo was a brand of brightly-colored fluorescent paint, and how this song chronicled the career of a famous LSD chemist named Owsley. But this was clearly too much information. He did, however, appreciate my explanation of the origin of the group’s name: Steely Dan was the moniker of a steam powered dildo in William Burroughs’ book “The Naked Lunch.” (I was always so happy that I could talk openly with my parents about anything and everything.)

I guess Daddy was a rocker at heart. He liked all the upbeat tunes of the day: Huey’s “The Heart of Rock & Roll,” J. Geils’ “Freeze Frame,” The Stray Cats’ “Rock This Town.” But his favorite song during the two years we spent on our highway odyssey was John Mellencamp’s “Jack and Diane.” He loved little ditties like that. Oh yeah, life goes on, long after the thrill of living is gone. Those words didn’t mean much to me back then, when I was 21 and my dad was strong as an ox and seemingly invincible at 54. I’m the same age now that he was then. And I switch to another radio station every time I hear the opening chords of “Jack and Diane.” It breaks my heart.

Daddy, like Mom, encouraged and fed my childhood rock-n-roll obsession. At least once a week, he stopped by the local record store and surprised me with a 45 single – often a song of his choice. I loved side A and side B of every record he brought home to me, and I still own every one of them: “To Sir With Love” (and its fab flip side, “The Boat That I Row”),” Judy in Disguise (with Glasses),” “The Airplane Song,” “Ode to Billy Joe,” “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” “Winchester Cathedral,” “Snoopy vs The Red Baron,” “Sugar Town,” “Georgy Girl,” “I’m a Believer,” and so many more. He loved Joe Tex’s “Skinny Legs and All” and would play it over and over again on my Sears “Silvertone” record player, laughing like hell.

We browsed through the record bins in department stores while Mommy shopped. It was during those times that I began building my vast collection of Beatles LPs and singles. I never came home without a record. Daddy loved looking at the album covers, even if he wasn’t familiar with some of the bands or songs. When I couldn’t decide which of several Monkees albums to buy, he pointed to the band’s first LP and said “I like the cover on this one.” To this day I cherish that Monkees album because he picked it out. And I’ll never forgot how he consoled me, when I cried my eyes out for five days straight after John Lennon was murdered.

We browsed through the record bins in department stores while Mommy shopped. It was during those times that I began building my vast collection of Beatles LPs and singles. I never came home without a record. Daddy loved looking at the album covers, even if he wasn’t familiar with some of the bands or songs. When I couldn’t decide which of several Monkees albums to buy, he pointed to the band’s first LP and said “I like the cover on this one.” To this day I cherish that Monkees album because he picked it out. And I’ll never forgot how he consoled me, when I cried my eyes out for five days straight after John Lennon was murdered.

My Dad was a proud Leo. He had a bigger-than-life presence and an even bigger heart. He would have loved the fact that I created a rock-and-roll blog, and that I dedicated this article to him – posted on the Internet for all the world to see. I love you Daddy. Thanks for everything. Oh yeah, life goes on, long after the thrill of your fabulous earthly presence is gone.

In memory of Fred D. Spiardi

August 4, 1928 to October 7, 2003

© Dana Spiardi, August 4, 2014

]]>

So, like the rockers who inspire me, I thank my mom for allowing me to develop my rock persona. On this Mother’s Day, I want to thank her for all the things she never did.

Dear Mommy:

Dear Mommy:

You never told me I couldn’t buy a record.

You never told me I couldn’t read certain books.

You never told me I couldn’t stay up late on a school night to see something special on TV.

You never forced religion down my throat.

You never told me that having a boyfriend or a husband or a child was “the thing to do.”

You never told me to “fit in.”

You never told me I couldn’t buy those $19 jeans that seemed so expensive back in 1973.

You never stopped me from wearing a rhinestone-studded “Sexy Bitch” necklace to school in 11th grade.

You never berated me for those poor math grades.

You never told me what to study in college.

You never made a big deal about money or social status or popularity.

You never encouraged me to join sororities or clubs because it would help me get ahead or find a husband.

You never told me to just ignore the panhandlers and buskers on the street.

And, even if you did tell me to turn down the volume on the stereo, you never told me to turn if OFF. You never closed your mind to the music or the art or the weirdness that I loved so much. You never gave up on me, even during my stoney end days. I love you, Mommy. Happy Mother’s Day.

Here’s a video that I made for Mommy, featuring the music of her favorite performer, Louie Prima: “Hey, Dig That Crazy Chick.”

Dig That Crazy Chick: My Mom, Helen Spiardi from Hip Quotient on Vimeo.

© Dana Spiardi, May 13, 2012

]]>